Every week, I write about international business, politics, or finance for the average Joe, 王, Silva, Rodriguez, Tesfaye, or Tan to show how our economies are more interrelated than one would think.

Today’s Topic: Luckin Coffee

Early Days: Rapid Expansion

Anyone who was in China in 2018 remembers how Luckin Coffee appeared on the scene. I recall stumbling upon it one afternoon while strolling around a Beijing mall.

“I need to order on my phone!? But I’m talking to you. Can’t you just take my order?” I asked the woman behind the counter.

The concept was bizarre. Paying for a coffee that first time seemed like a lot of work. I had to wait a minute or two for the app to download before I was even capable of connecting my Alipay to make an order. If the company was trying to sell convenience, it didn’t seem so at the time.

But don’t forget. This was the era when ride-hailing apps were truly beginning to wipe out the remaining taxi companies still holding out. Luckin was brave for mixing the new business model with coffee, another growing trend in China.

Within a month, I was seeing the business open up in central Tianjin. It wasn’t long before it seemed every elevator had that same blue and white ad telling me to purchase the coffee. Indeed, today we have the data to know that between January 2018 and March 2019, Luckin opened 5.2 stores per day.

In 2019, the company truly showed the world they meant business by surpassing Starbucks in the number of stores in China. Not just this. Despite being only two years old, Luckin attempted this year to enter its first international markets, the Middle East and India, by partnering with Kuwait-based The Americana Group. While these plans fell flat due to internal turmoil and leadership plans, other countries were beginning to notice. That same year, for example, Flash Coffee was founded in Singapore in an attempt to copy Luckin’s business model. Zus Coffee and Kopi Kenangan Coffee did the same in Malaysia and Indonesia, respectively. Regardless of commentary disparaging the new Chinese coffee chain as cheap, it was undoubtedly beginning to cause quite a stir.

Perhaps it was due to this rapid growth that Luckin decided in May of 2019 to debut on Wall Street, where it went on to surge 50% to $25 before falling 39% the following week. Whatever investors thought of the company’s fast expansion, however, the hype was stopped in its tracks in 2020 when the cafe chain was caught inflating its sales revenue. Luckin then hit a low of $2.16 that May. Eventually, Luckin was able to restructure itself and emerge from bankruptcy, but it would take three years for the company to reach its initial offering.

COVID-19: A Blessing in Disguise?

Oddly enough, there is an argument to be made that the pandemic actually helped Luckin Coffee regain its momentum. Remember, 2020 was before China’s zero-COVID lockdowns. In fact, at the time, it seemed the East Asian nation was faring better than Europe and North America. By summer, most workers there had returned to the office. Chinese stocks looked safer. Furthermore, Luckin was capable of riding that crazy year when it seemed every stock valuation was going to the moon. Even when this party ended in late 2021, Luckin began to bounce back the following May, five months earlier than American tech giants like Meta and Alphabet.

Indeed, it seems the same could be true even in 2022 when Beijing’s policies became stricter. As Tencent was falling, Luckin remained persistent, even surpassing its initial price offering by the end of the year. How did it do this? One WeChat article believes cutting labor costs and using cheaper, more local ingredients did the trick. The number of full-time managers was reduced too. Even part-timers were hired. Instead of focusing on opening more stores, underperforming ones were closed. Rather than creating new menu items, Luckin honed in on hit products like its coconut latte.

Perhaps part of Luckin’s success here was due to the overall Chinese economy’s bumpy recovery. Basically, every Chinese company gained in early 2023 following the end of COVID lockdowns before falling in the late spring after global investors realized consumers weren’t revenge spending as much as expected. Yet, even after this, Luckin continued regaining ground, and in a much more stable fashion than in 2020. One must ask whether cost-conscious consumers, anxious about the future, actually gravitated towards Luckin due to its cheaper prices. Regardless of how horrible 2022 was for China, it was perhaps the year the coffee chain proved it was here to stay. Not only did Luckin Coffee turn an annual profit for the first time, exceeding 1.156 billion RMB, but it also increased its monthly active customers from 9 million in Q1 of 2021 to 24.6 million in Q4 2022. In 2022, 2,190 new stores were opened, followed by 478 in January 2023.

A New Challenger: Cotti Coffee

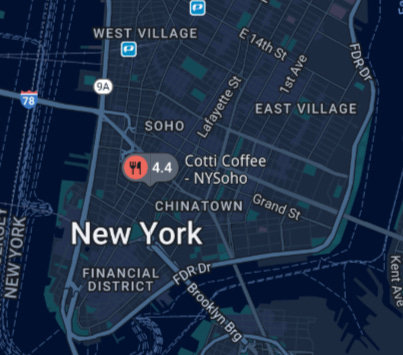

Not everything was smooth sailing, however, especially since other companies were beginning to copy Luckin’s model within China. Cotti Coffee, for instance, was founded in late summer 2022 by two ex-Luckin executives to offer coffee for just 9.9 RMB or $1.38. One of these founders was none other than Lu Zhengyao, the same Zhengyao who was held responsible for Luckin’s financial fraud in the past. With someone so knowledgeable of Luckin working behind the scenes, Cotti easily replicated the chain store’s business, with some stores even using the same coffee machines. According to one WeChat article, Cotti reached out to Luckin employees and managers in its early days, offering them higher salaries and positions if they joined. Anyone who signed up for the new company was required to read Luckin’s financial reports every quarter and know the competitor’s menu back to front.

In the past, Luckin’s main competitors in China were Starbucks, other premium brands like Costa and Pacific Coffee, small local cafes, and cheap convenience store coffee. While Luckin had been able to compete with the premium brands on price and appear better than 7/11 or Family Mart through the ability to order on the phone beforehand, the emergence of Cotti was a game-changer in that now Luckin needed new ways to differentiate itself. Cotti’s strategy of opening stores close to Luckin (something Luckin once did with Starbucks) to attract customers not interested in waiting didn’t help. Additionally, Cotti took advantage of Luckin’s refusal to franchise the business. Many business people across China who were eager to manage a coffee store of their own, but unable to do so due to this policy, were poached by Cotti instead.

Looking at Luckin’s stock between March and June 2023, an investor may be correct to ask whether the company’s price fell during this period solely due to declining hopes about China’s overall economy. Cotti’s arrival was probably another primary culprit, as Luckin was forced to lower its prices to compete, leading to a fall in revenue and profit margins. This was the period when Cotti pushed marketing campaigns featuring cheap summer drinks. The new brand saw a huge jump in orders at the expense of staff members complaining about hand cramps and heavy subsidies to keep shops afloat in the hope of victory in the long run. While Luckin took a hit financially to hold its ground, other smaller competitors closed shop, unable to compete in the price war. One instant coffee brand saw its sales plunge by 70% while even Starbucks began offering discount vouchers.

Interestingly enough, Luckin’s stock began to recover after all this around the same time Cotti’s strategy started losing steam. Following summer 2023, sales plummeted, falling from 270 cups per day in October to 150 in February. In turn, 826 Cotti stores closed, over 100 employees were fired, and R&D teams were cut by 50% during this period. Put simply, the company could only rely on cheap prices and heavy subsidies for so long before everything started catching up with it. In early 2023, Luckin co-founder Jinyi Guo exclaimed in an interview that he didn’t fear Cotti and that Starbucks was the company’s only real rival. Of course, this was before the summer price wars, and regardless of whether Jinyi’s opinions eventually changed because of this or not, by the end of 2023, it seemed apparent he was right to remain calm. By 2024, Luckin had not only left its financial struggles and negative image far behind. It also appeared like the path to victory was all but assured. Today, I often read from foreigners living in China that Luckin’s coffee is better than Starbucks's.

We cannot assume that the rivalry between Luckin and Cotti is over yet, however. In recent months, Luckin reiterated its commitment to a low-price strategy. Yet, this use of the word “commitment” ignores that Luckin’s prices have gone lower. Until now, Luckin has never stooped to selling coffee below 9.9 RMB a cup. Could this new territory be partially due to Cotti’s May 1st flash sale that saw it skyrocket to being the #1 coffee brand on Taobao within 24 hours, with orders up nearly 10 times? Its JD sales for that week also exceeded 40 million orders.

Yet, it is clear that Cotti’s image in China has been hurt. Scan the social media app Xiaohongshu, also known as RedNote. in English, and you’ll find posts related to a trend where users must “spot the Cotti Coffee sign” among other company logos. One WeChat article even calls Cotti’s business model of opening within convenience stores and other already-established businesses “parasitic”. Today, the brand is attempting to transition away from the “store within a store” model to one where Cotti itself serves as the primary venue, allowing other companies to set up shop within its premises.

No Longer Just a Chinese Company: Singapore, Malaysia, & the United States

Another reason we cannot count Cotti out yet, however, is that it had a head start over Luckin internationally. While both expanded internationally in 2023, Luckin has been much slower to do so. To date, Luckin has opened in Singapore, Malaysia, and the United States. Cotti can be found in 28 countries. This includes those three countries, as well as South Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Qatar, and Australia. While I do not have time today to go into depth about Cotti’s business globally, it will be interesting to see how the international and domestic battlefronts interconnect in the future. After all, according to Seeing the Unseen, many Chinese entrepreneurs have taken inspiration from Mao’s tactics in the Civil War, in particular the concept of “surround the cities from the countryside”. If Europe and North America are the cities and the Global South the countryside, it would appear Cotti is in line with Seeing the Unseen’s research, while Luckin is trying the opposite attack plan.

It’s my personal opinion that in the English and Chinese-speaking worlds, as well as Europe, Luckin Coffee is more well-known and has better branding than Cotti. After all, Luckin is a publicly traded company while Cotti is not. If anyone reading this has drunk at a Cotti establishment outside of China, feel free to drop a comment below. Next week, I will double back and connect Cotti’s business to Luckin’s internationally.

For now, Cotti’s international model can still provide a useful comparison to Luckin’s, especially in how it relates to my overall goal of these writings: to show how our economies are more interconnected than one would think. Given that both brands went abroad in 2023 when the price war was intensifying, it can be assumed that at least Cotti began looking internationally to act as a buffer for its China business. For Luckin, it is harder to say, considering it was around for half a decade more. It may have had these plans in its back pocket long before other Chinese coffee brands started encroaching on its turf.

Nevertheless, one divergence between the two brands is their appetite for replicating their China model internationally. While Cotti has followed a similar strategy built on speed and scale, Luckin is being more cautious. For example, its Singapore stores initially opened offering drinks priced at S$0.20 before moving on to prices more in line with Starbucks. According to 2023 data, Luckin’s drinks ranged from S$4.80 to S$6.80, while Starbucks’ prices were between S$4 and S$9. Furthermore, while the company has adhered to its small, takeaway model, it has also tried a new “relax” concept where customers are offered sit-down spaces at least 1,200 square feet in size. Although some of these locations only have 15 seats.

We may also ask whether it isn’t a coincidence that Luckin chose Singapore for its first international locations. Of course, the city-state has a large population of people who trace their ancestry to China. This means that there was a higher chance individuals were aware of Luckin before it arrived. Yet, it’s also a global metropolis. With a cafe in Changi Airport and Guoco Tower, Singapore’s tallest skyscraper, Luckin probably hoped there was a higher chance that more people from around the world would come in contact with their coffee and remember their brand. In other words, while Cotti has continued to flood the market to be seen by as many consumers as possible, Luckin has focused on scarcity. With 30 stores in Singapore today, Luckin has attached its own branding to the vibe of the country.

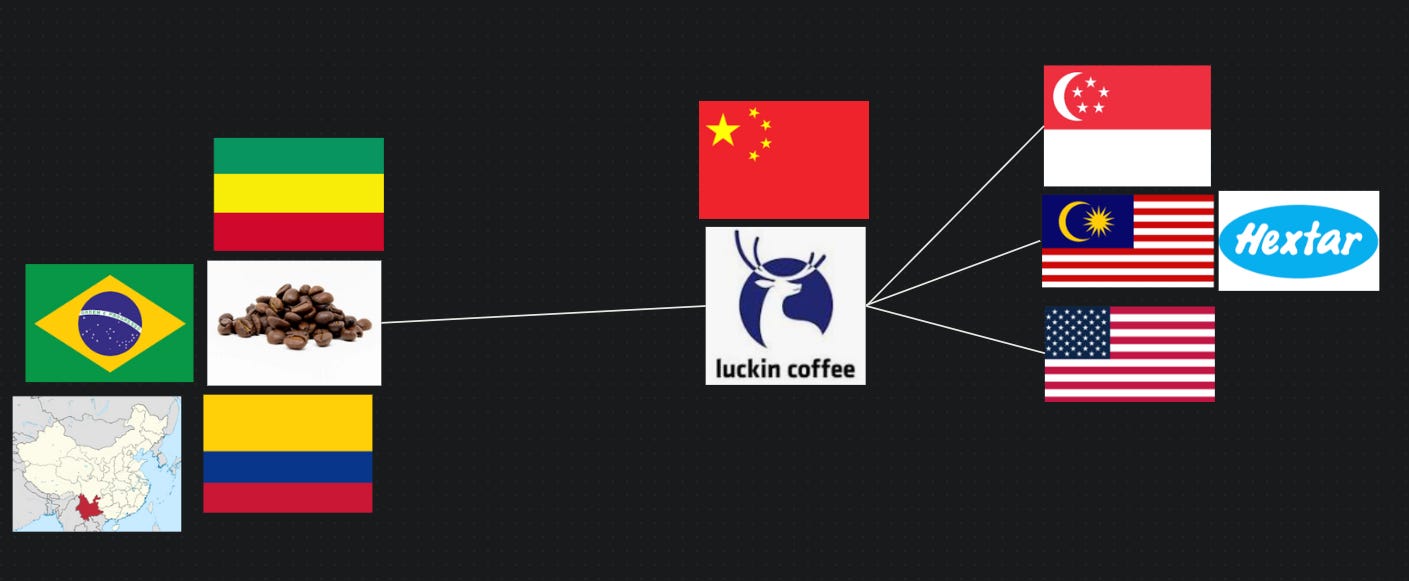

This appeal to sleakness shouldn’t be overlooked.. Remember, the “Made in China” label still haunts any company from the Middle Kingdom. It will be another few years before Chinese brands can sell products abroad without consumers associating “China” with “cheap knockoffs”, especially in developed Western countries. This is important given that the coffee beans Luckin is using in Singapore are still sourced from coffee farms in Yunnan province. Perhaps Luckin had all of this in mind when it chose not to follow in Cotti’s footsteps. If Luckin had mimicked Cottia and gone to South Korea or Japan, countries that are still considered “more developed” than China, would the two companies have been compared to one another more, leading to its branding taking a hit?

In this way, the cultural similarity between China and Singapore plays to Luckin’s advantage too. It is well known that Singapore is becoming the Switzerland of Asia at the moment, choosing to remain neutral in many global affairs. Therefore, there was less of a chance that politics would tamper with how consumers there thought of Luckin. Like many other Chinese companies that have moved bank accounts and head offices to Singapore since the pandemic, success in this small nation will help Luckin erode any friendly fire events that may occur in the future.

Albeit, sometimes politics have worked in Luckin’s favor. Was it simply a coincidence that Luckin chose to enter its third market, Malaysia, earlier this year after Starbucks suffered a $15.1 million setback over the last six months of 2024, following consumers' boycotts of the American chain over the USA’s handling of Gaza? Whatever the answer to that question is, it is clear Luckin is following a similar strategy in the federal constitutional monarchy as Singapore that aims to place the coffee maker as a mid-to-premium brand. Although its partnership with Hextar Industries Berhad (HIB), a company with no experience in the chain restaurant sector, may seem unusual at first, it's clear that Eddie Ong, HIB’s major shareholder, possesses extensive business acumen. With two decades of experience in a diverse range of industries, including chemicals, real estate, and consumer goods, Ong may know everything there is to know about Malaysia’s economy. Still, his company’s stock hasn’t had the best two years.

This finally brings us to the United States, the newest market Luckin entered this month. Based on the little it has done thus far in the country, it would appear the company is continuing to be aware that it’ll need to be strategic. By making the US its fourth country of entry, Luckin is not following the same path as other Chinese companies, such as Xiaomi or BYD, which preferred to enter easier markets first. Even if this move loses boldness when we remember that Cotti already has stores in New York City and California, we shouldn’t ignore where the two brands have opened. Cotti is in Flushing and California, two places with more Mandarin speakers. Even its Manhattan location is next to Chinatown. Luckin, on the other hand, has aimed more north.

Maybe none of this happened purposefully. Nonetheless, we should still ask whether a store closer to Chinatown, let alone Cotti, will hurt or help Luckin. The one location is still close enough to Mandarin speakers that it’ll benefit from people already aware of the brand, as it did in Singapore. Yet, it’s also far enough away that its branding has room to breathe on its own. I’m probably overthinking this, but we can never be sure when there are already X posts, both sarcastic and genuine, calling Luckin a national security threat. One post, for example, exclaims how the company’s requirement of its customers to order on an app could send data to Beijing. Given the past few years and conversations over TikTok, one can never be too sure that statements like this won’t become more mainstream. There are also those making the argument that politics won’t truly enter the conversation unless Luckin takes a large enough market share from Starbucks.

Yet, Is There a Political Dimension to Luckin?

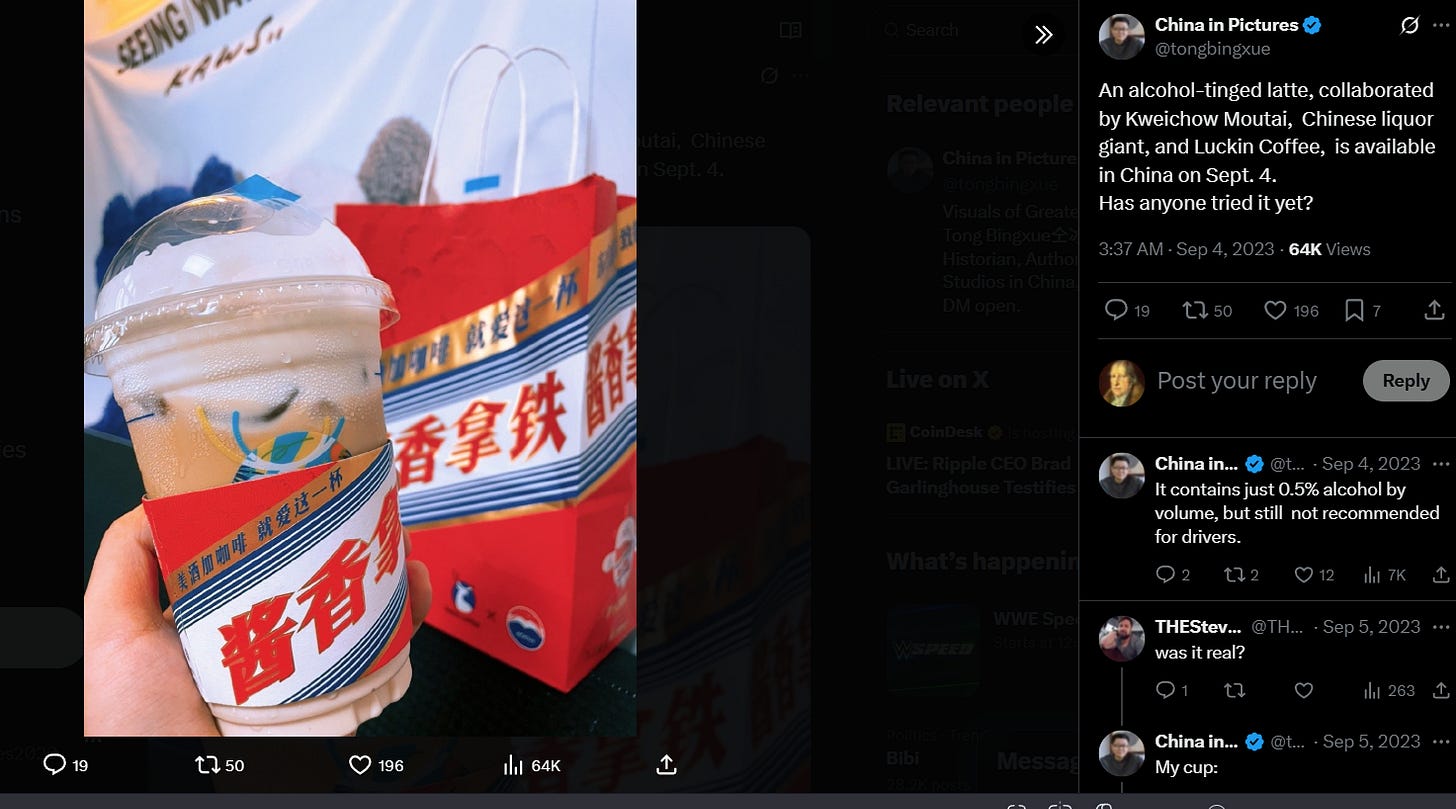

Regardless of whether any of this actually occurs, it wouldn’t be insane to ponder the broader political dimensions of Luckin’s international expansion. After all, with its beans sourced from Ethiopia, Beijing’s “non-interference” policy may eventually be put to the test, especially if the country is a key outlet for Chinese electric vehicles’ push into Africa. During the East African company’s recent civil war, for instance, coffee prices became inflated, something a company like Luckin, which has advanced due to cheaper prices, may not want. On a grander level, Luckin’s success internationally may serve as a soft power role in the long run, meaning the Chinese government has an interest in ensuring stable supply chains. This may seem extreme, but consider how the coffee brand has benefited from partnering with other Chinese IPs, such as Black Myth: Wukong and Maotai Baijiu, over the past few years. If Luckin continues to expand into the lives of workers who drink coffee on a daily basis, will the company help open the door to success for other Chinese brands in the future?

Then there’s Colombia, a country that was recently hit with Trump’s 10% tariff. As another country from which Luckin sources, it will likely be a key player in the company’s American strategy. Yet, will the bad timing of this with Donald’s policies prevent Luckin from offering discounts in the United States? Additionally, as Luckin and, to a similar extent, Cotti expand globally, will Colombia become less reliant on exports to the United States? Currently, 40% of the South American nation’s coffee output goes to its northern neighbor, and coffee accounts for 7% of the country’s GDP. If Luckin’s CEO is correct that Chinese consumers will increase their consumption from 10-20 cups of coffee a year to 100-200 cups in the next two decades, what will this percentage look like in the future? What function is Luckin playing in pushing this shift, and how will this change influence Colombia’s foreign policy? Last year, Colombia’s coffee exports increased by 17%, mostly driven by China, for example. In 2019, the East Asian country ranked as Colombia’s 6th most important coffee market. It was ranked 2nd for the first time in Q1 of 2024, a position analysts believe it will eventually retain overall.

We could ask the same questions now that Luckin has agreed to purchase $2,5 billion worth of coffee from Brazil between 2025 and 2029. Just look at how that Portuguese-speaking country has helped soften the blow of soy exports bearing the brunt of the trade war. Hell, apparently, some farmers there have even been happy that Trump has thrown a wedge between the US and China. One could also argue that trade tensions have even improved Brazilian-Chinese relations over the past decade. With Luckin’s increasing reliance on Brazil, what new leverage will Brazil, China, and the USA have over one another?

Again, this is all very abstract, but one can still ponder.

Another dynamic to consider is that China’s coffee industry is already a lot more sustainable than the United States’s, and Luckin has been at the helm of this transformation. Since 2021, for example, it has had a small roasting base in Fujian province. There is also a second base in Kunshan, Jiangsu, and a bean processing plant in Baoshan, Yunnan. Since the beginning, Luckin’s control of the raw materials and supply chain necessary for brewing coffee has been a core reason the company has been able to sell such affordable drinks. Trump can try all he wants to reduce the trade deficit, but the United States simply doesn’t have the same climate as China or Colombia for producing beans, a practice introduced to Yunnan as far back as the 19th century. If Luckin is capable of gaining ground outside of its own habitat while offering drinks that are 100 percent sourced from Yunnan, perhaps we will see more tourists wanting to visit the southwestern province. Thus, another soft power win.

The influence of coffee on soft power works in the reverse too, by the way. A recent article entitled “How China’s coffee culture is responding to trade tensions”, decribes how Chinese brands like Luckin Coffee have actually benefitted from Trump’s trade policies. Similar to what we saw in Malaysia as a result of Gaza, big talk and confusing messaging around tariffs have pushed some Chinese to skip American companies for local ones. While this article doesn’t provide exact data or specific policies related to how the trade war has benefited Luckin, it suggests that overly strong America-first rhetoric may not benefit companies like Starbucks that get some revenue from China.

Is Luckin Really a Threat to Starbucks?

Nevertheless, Starbucks is a company to watch as Luckin tests its feet in the United States. Hot on the heels of the news that it’s considering selling a controlling stake in its China business, the Seattle-based multinational coffee chain saw same-store sales decline by 2% in the USA and 8% in China. This April, Starbucks also reported that its quarterly profit was half of what it was a year before. The most interesting development about this, however, is that, in order to turn itself around, the company claims it will be returning to its earlier business model of trying to provide a “third space” to foster human connection. This is the exact opposite of Luckin’s easy pickup model.

Consider then all of this in the context of America’s post-COVID culture where medicine magazines are decrying a loneliness epidemic and consumers are spending more time at home. Even if Luckin follows its old tactics of opening locations 100 meters from Starbucks, is its speedy pickup-and-go model arriving at the proper time? Given New York’s image of being a city of workaholics, I bet this won’t be a problem, even if Starbucks’ new approach better appeals to the current cultural milieu. Yet, with the company following its Singapore strategy of not trying to appear as a cheap alternative, will the company be able to differentiate itself from competitors in an already saturated market? Despite launching its two stores in New York City with a $1.99 promotion and additional discounts for those who download the app, Luckin’s prices still range between $3.45 and $7.95. In general, the company’s drinks are 20% less than those of Starbucks. For example, Luckin’s Americanos are priced between $3 and $5, compared to Starbucks', which are $4.75 and $5.75. Perhaps that dollar or two will mean something to some people. It may just be enough of a discount to not make Luckin appear too cheap. Yet, it may not even be capable of doing this, given the higher operational costs in the US.

One tactic Luckin is trying out to create branding is offering unique flavors catered towards the American market, as well as other unusual drinks it has become famous for. These include the jasmine and blood orange cold brews as well as coconut lattes. This wide range of choice is already getting the Chinese company compared to Dutch Bros, another coffee chain that has been growing on the West Coast.

An additional cultural nuance to pay attention to is how easily Luckin’s model will adapt to the United States. Social media posts about data and national security threats aside, will Americans be interested in ordering drinks from their phone? During my 5 and a half years back in the country, it doesn’t seem Apple and Google Pay have caught on to the extent Alipay and WeChat Pay have in China. According to YouGov, only 17% of US adults use mobile payment apps for in-store purchases. This isn’t the only technology gap between the two countries. Customers apparently needed help understanding how to use a QR code in Luckin’s New York stores. Part of Luckin’s success over the years is how data collection has made it easier to track inventory and send personalized ads to customers. How will the company retain brand loyalty if customers are more wary of mobile payments?

Then there’s the difference in human geography. Americans live in rural towns where dining is more preferred. Luckin was built for China’s metropolises. Luckin has not announced any plans to open new locations in the US and says it wants to move cautiously. If I were working with them, I’d probably suggest focusing on highways, although the question then would be whether that would tarnish the company’s branding. Luckin wouldn’t want to be too associated with truck spots. Still, smaller roads on the way to work may suffice. Maybe in the United States, they will use their Singapore “relax” model more. Although so far, their New York locations have just three tables.

Finally, given my background in localization, I am going to keep an eye on Luckin’s localization efforts. I’ve already caught one English mistake. Does the message really get lost if there is no “for” after “makes”? No, but if Luckin is wanting to escape from the negative appeal of “Made in China” that still exists, especially in the USA, and it is still known as the company that beat Starbucks due to cheaper coffee, every little mistake will count. Hey, I’m happy to help Luckin if anyone important comes across this article! (Yes, my Substack is somewhat an ad for myself.)

Despite my concerns, I was glad to see Business Insider put out a pretty balanced review of Luckin. To the self-proclaimed coffee lover writer, Luckin’s coffees were not the best but still good enough that Starbucks should be paying attention. The article is also filled with reviews from other customers happy that the use of fruit suggests less syrupy drinks and that the prices are unmatched in the city.

Success in the United States will also be pivotal for ensuring Luckin’s different approach to global expansion works out. In fact, it seems the choice to enter the North American country early on rather than later has similar thinking behind it to what drove Singapore to be Luckin’s first overseas market. To Luckin, the United States is a soft power hegemon. Its movies and TV shows are loved all over the world. Brands that succeed here are more likely to find victory elsewhere too. American influencers also have a huge impact on social media. By opening stores in the US, Luckin hopes the USA’s branding rubs off on its own.

Conclusion

So, that’s a general overview of mostly everything I can find in English and Chinese on Luckin’s business. In terms of finance, I am cautiously optimistic about the company’s stock. It has rebounded from its mistakes a few years ago, even coming out stronger, especially since Starbucks seems to be a waning force in China. Now, it doesn’t just have room to grow in its home country, but elsewhere too. Yet, my caution comes from the cultural differences and saturated market in the United States. Will Starbucks be able to rebrand itself? Will Luckin’s model work in a country of small towns and individuals not preferential to ordering on a phone? In China, will Luckin be dragged back down by Cotti? If anything can be learned from Luckin’s almost decade in the business now, it’s that the coffee chain knows one key doesn’t unlock all doors. Plus, the brand is far from being a well-known name in the United States yet. It may be a good bet to invest in the stock before that changes.

These mechanisms of Luckin’s business also reveals how people from different countries are interconnected too. While Luckin is a Chinese company, it would not be able to exist without the help of individuals from other countries. Ethiopia, Colombia, and Brazil provide coffee beans alongside Yunnan province. Singapore and the United States offer branding tools to familiarize more humans with Luckin’s products. Even for Malaysia, the presense of ethnic Han consumers reveals that business is built on the back of ties that go beyond nationalism. These interconnections may not always be so rosy, however. Just as we have seen both more opportunities for collaboration and tension arise from increased trade between the United States, Europe, and China more over the past 40 years, so will Luckin’s expansion maybe follow a similar route, even if it is very subtle. Will Luckin be able to help chizzle away further at the “Made in China” stereotype, assisting other brands in the future to have it easier? Will employees who make their way up the ranks in the company find their incentives at odds with one another if politics ever gets in the way of business? Will Luckin lead the charge in promoting China’s importance to coffee supply chains, altering relations between countries at the same time?

Humanity is one complex web of relationships and history is often no simpler. The best we can do is try our hardest to understand how everything is connected, from the smallest individual to the largest corporation.