Every week, I write about international finance, business, or politics for the average Joe, 王, Mohammadi, Martin, 김, 佐藤, Smith, Hernández, Silva, Cohen, or Garcia to show how our economies are more interconnected than one would think.

Today’s Topic: Iran’s Auto Industry

President Bush Sr.’s engagement policy and the similar Wandel durch Handel strategy (change through trade) hinged on the idea that, through investing in China, it would adopt democratic principles similar to South Korea and Taiwan. The problem with this thinking, maybe, was that it overlooked how relationships work. Looking at the state of the world today, as European and North American leaders realize how reliant their countries are on China for necessities like rare earth minerals and prescription drugs, it would appear that Foucault’s idea that power is not merely a top-down affair is correct. After 35-plus years of trade, the world has been changed by China just as much, if not more, than the Middle Kingdom has been by others. When we talk about other events moving forward, it’s best to keep this dynamic in mind as much as possible.

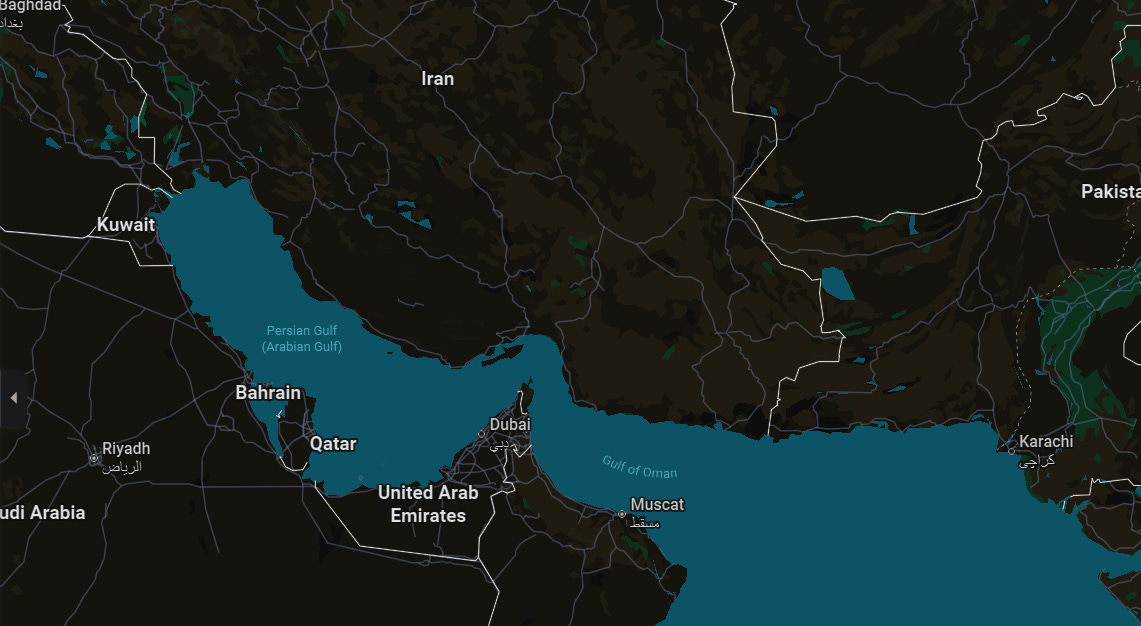

Take Iran over the past few weeks. 4 days into the so-called “12-Day War” between Israel and Iran, the Wall Street Journal and others were pointing out how 90% of Iran’s oil exports go to Chinese refineries in Shandong province that operate independently from state-owned oil companies. Yet, while roughly 13.6% of China’s imported oil comes from Iran, if the Islamic republic had closed the Strait of Hormuz due to hostilities, it would have cost China even more, given that it gets 30% of its gas from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Upon hearing this news, I was reminded of a recent interview where Peter Zeihan discussed how easily it would be to cut the Middle Kingdom off from the resources it needs. A few weeks later, President Trump announced on Truth Social that, “China can now continue to purchase Oil from Iran. Hopefully, they will be purchasing plenty from the US, also.” This begs the question whether this intention was in the background since the beginning, especially since tariff talks are still going on.

Whatever the case, I don’t believe this will be the last time we hear about Iran’s role within broader international relations, especially since it seems the government there has been warming to electric vehicles (EVs). As recently as early last year, the country’s leaders were refusing to import any non-gasoline automobile, a policy some analysts believed was due to the Persian state having a monopoly on the domestic car industry. In 2023, while other countries were racing to catch up with Chinese electric vehicle companies and Tesla, not a single unit of the 1.2 million vehicles produced in Iran was electric. The government claimed that their resistance stemmed from fears that Iranian electricity’s reliance on thermal power plants is not environmentally friendly, even though the country’s domestically manufactured cars consume 16 liters per 100 kilometers, twice the global average. At the time, the West Asian theocracy could have benefited from moving toward new technology. Beginning in mid-2022, a gas deficit had made the nation reliant on imports and short on gas. Not only this. Tehran has been one of the world’s most polluted cities for a while. Electric vehicles would have tackled both issues, with charging costing a quarter the price of filling up on gas.

Perhaps it was because of these issues that new policies have been rolling out this year. In April, for instance, a directive was put out demanding that all new fuel stations include one electric vehicle charging unit. This comes alongside the goal of replacing gas vehicles with electric alternatives. According to the most recent information, Tehran now has 189 electric buses and 1,752 electric taxis in operation.

Here is where China comes in. According to Iran International Newsroom, a secret car deal was signed last April allowing the East Asian nation to export $3 billion worth of electric vehicles into Iran, including buses. This should come as no surprise, seeing that Iran was one of the first markets Chinese brands ever entered back in the early 2000s. Whenever sanctions have been placed on Iran over the past two decades, pushing out other foreign competitors, these companies have only benefited. It’s important to note, however, that in 2025, the playing field is much different than what it was 10 years ago. While in the past, Chinese brands were practically unknown outside their home country and used Iran as an easy new market, given the steeper competition elsewhere, many of the companies with a long history in Iran are making inroads even in Europe today.

Take Chery, for example, a car company hailing from Anhui province. After entering Iran in 2004, the brand went on to form a joint venture with domestic Iran Khodro, where the two made an initial $200 million investment to manufacture 100,000 units over the next two years. By 2007, this partnership had expanded to include Canadian investment firm SOLITAC, which launched a $370 million factory in Babol. Today, Chery is the largest foreign manufacturer in Iran, where 180,000 of its units are on the road. It is currently completing an industrial park with plans to quadruple production and sell 100,000 cars per year. In 2004, Chery’s international endeavours had only begun three years prior with exports to Syria. Even in 2014, the company’s annual export sales figures only stood at 108,238. In 2024, this had multiplied by almost 10, hitting 1,144,588.

Chery’s markets have increased a lot too. Last year, the company created a joint venture with Spain’s EV Motors to build cars locally. Just this week, the Guardian announced that the brand was actively considering opening its second European factory in the United Kingdom. In South America, Chery entered Mexico in 2022, having already been in Brazil since 2011, where it is the 11th best-selling passenger vehicle brand. While this may not seem like much yet, consider how Chinese brands overall now hold a 20% market share in Mexico. The reality, then, is that Iran is no longer simply the backwater market these companies entered without any other choices, but a smaller piece in a larger puzzle.

Does that mean the country’s automobile market is in a better state? No, but it certainly means one should be surprised we’re still seeing titles like “Stuck in the 80s: Why Iranian Cars are All From a Bygone Era” having sentences like “From aging Peugeots to Chinese imports, Iran’s auto industry tells the story of a country improvising under pressure—and proud of it”. My disagreement is not with Iran having an aging fleet but that Chinese imports should still be used as an argument to show how backward the economy is. If the country is indeed placing more focus on electric vehicles, with China’s help, what does this mean for where the country will be in five years? And, what does such an approach mean compared to the US government’s current antagonism toward electric vehicles?

In 2025, Iran’s car industry is still dominated by state-owned Saipa, with France’s Peugeot in second place and state-owned Iran Khodro in third. However, this misses the importance of joint ventures with Chinese brands, which now produce 1/5 of vehicles in the country. These partnerships include Modiran Khodro with Chery, Kerman Motor with JAC, Bahman Group with Chery and Dongfeng Motor, Arian Pars Motor with Dongfeng, SAIC with MG Pars, and Pars Khodro with Leapmotor. Given Changan ended its partnership with Saipa earlier this year, and the Iranian government’s goal of electrifying the country, one must wonder whether the rankings in the country will change soon. Remember, while governments with more grip have their downsides, one upside that is sometimes mentioned is the ability to get industries moving when needed. A WeChat article from the 15th of June exclaimed that Chinese brands are racing towards 20% market share in the country, mostly due to the affordability and newness of the vehicles. Given that Bloomberg believes the US may lag behind the global average of EV adoption until 2040, is there a possibility Iran may outpace the United States?

Maybe that’s a question based on strong assumptions, but still, I think we should consider how an Iran reliant on Chinese EV manufacturers that are also advancing globally will impact international relations. Let’s say something similar to the Israel-Iran War occurs again in 5 to 10 years when Chinese EV companies have only increased their global footprint further. How will events play out? Will the US be better able to pressure China to persuade Iran to stand down by pushing European and South American countries to penalize Chinese companies if they don’t stop operations in Tehran? Yet, by that time, non-Chinese may also be more reliant on China for work, let alone cars and other products. Additionally, what would this mean if Europe’s support for Israel reaches an even lower level in the future?

At the very least, this turn of events should make policymakers reconsider the past 20 years. After all, if it weren’t for sanctions, perhaps events would have played out differently. Maybe Peugeot, Toyota, Kia, and others would have started investing in Iran’s electric vehicle infrastructure before China. Perhaps there is still a chance for this. France’s Peugeot is still second in the market, so it has brand presence. However, a new Peugeot remains more expensive than Chery, costing 5.5 times an average Iranian worker’s annual salary. Chinese sources say Korean imports are rising, though I cannot find any other evidence of this besides one in English. In July last year, Iran’s government began allowing imports of second-hand Japanese, Korean, and European cars.

It will probably be an uphill battle for some of these brands to compete with Chinese rivals, but in light of the fact that the world today is very different from even the first Trump administration, it may be smart to consider a more pragmatic approach similar to the engagement policies of Ronald Reagan, Bush Sr, or Nixon. Last year, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies published a report, which then appeared in the news, arguing that Trump needed to pressure Chinese car companies to sever ties with Iran. While it is uncertain whether the US president or his team has taken note of this policy yet, fear of sanctions was one reason Changan ended its relationship with SAIPA in February. Nonetheless, if we believe that Chinese companies will soon have 20% of the Iranian market, this is just one raindrop in an ocean. Moreover, Trump’s messaging about allowing China to buy Iranian oil may mean there is less likelihood of sanctions increasing. Of course, we never can be sure. Yet, if nothing is done, it may be worthwhile considering whether further sanctions would actually hurt the US and Europe long term. If the past is any use in understanding the future, it appears regardless of regulations, Chinese companies always have the drive to come back to Iran and regain market share while others stay away, fearful of it being a waste of time. Perhaps here is a place where the United States should hold off on penalizing its allies in the hope of a new engagement strategy emerging.

Still, it would be naive to think the events of the past few weeks and years could just be overlooked. This raises the question of how strongly Iranians associate Europe, South Korea, and Japan with the United States.